By Oxana Sidorova and Rebecca Campbell-Montalvo (contact rebecca.campbell@uconn.edu)

Funded by El Instituto and the Collaboratory for School and Child Heath at UConn, El Instituto graduate student Oxana Sidorova and Curriculum and Instruction Postdoctoral Research Associate Rebecca Campbell-Montalvo, along with colleagues in UConn Nursing (Ruth Lucas, Xiaomei Cong) and at the University of Denver (Miriam Valdovinos), conducted research in the months prior to the Covid pandemic in a local Connecticut Elementary school. The work, currently being revised to be resubmitted to AERAOpen as an invited manuscript examines healthcare access brokerage by school employees for immigrant Mexican and Indigenous Guatemalan farmworking families.

Nearly 20,000 Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers (MSF) adults live in the Connecticut River Valley region and commonly work with shade and broadleaf tobacco, fruit trees, or in nurseries throughout the state (State of Connecticut, n.d.), yet there is no verifiable data on how those with children are served by local schools. The research team conducted twelve exploratory interviews with parents speaking English and/or Spanish with at least one child enrolled at the school and school employees speaking English and/or Spanish who work directly with migrant and/or seasonal farmworking students at one of the elementary schools in Eastern Connecticut. Conversations with school employees showed that MSF students are in attendance at the school, and students from the school year 2019 when research was conducted were newly arriving immigrants with most from Guatemala, and many were Indigenous K’iche’ speakers. Interviewees explained that chain migration and church connections facilitated job searches for incoming migrant families and encouraged a continued movement of people to the area. In their interviews, parents and school employees talked about the various health care needs and concerns of families. Three major themes emerged from participant interviews: MSF family health needs, health care access brokerage, and employee barriers to brokerage.

Our research confirmed that MSF families have health needs that are often compounded due to their structural vulnerability. These needs included immunizations, vision, dental, mental health, and other concerns. Attending medical appointments and obtaining medication are often difficult for MSF families. According to the school staff and interviewed mothers, parents are often unable to take advantage of services due to personal reasons, financial issues, having to be at work, lack of transportation, and linguistic barriers. However, Nippawus’ main office and various school employees played a crucial role in brokering health information and health care access to families. In fact, a range of school employees worked together and prioritized families’ wellbeing and offered a generally cohesive approach to supporting families that often connected them to medical offices and community organizations. The finding that such a broad range of school employees – including its principal, the FRC workers, one administrative support staff member, its nurse, and one of its social workers – can address family health needs extends previous work that focused on specific sets of employees (i.e., Campbell-Montalvo & Castañeda’s [2019] focus on Migrant Advocates). The school employees’ brokerage through deep connections and relationships with local clinics is more pronounced than suggested in earlier research. Yet, there were barriers that hindered this brokerage, including a gap between families’ needs and school personnel members’ awareness of families’ needs as well as employee exhaustion and the sheer number of issues encountered by MSF families. Many MSF participants explained that they did not have health care resources or medical services at the schools from which they come, and parents are not expecting the school to provide that kind of support. To address brokerage obstacles, school staff found they must balance friendliness that they try to achieve in their relationships with families and keeping professional boundaries, in order to not burn out.

its principal, the FRC workers, one administrative support staff member, its nurse, and one of its social workers – can address family health needs extends previous work that focused on specific sets of employees (i.e., Campbell-Montalvo & Castañeda’s [2019] focus on Migrant Advocates). The school employees’ brokerage through deep connections and relationships with local clinics is more pronounced than suggested in earlier research. Yet, there were barriers that hindered this brokerage, including a gap between families’ needs and school personnel members’ awareness of families’ needs as well as employee exhaustion and the sheer number of issues encountered by MSF families. Many MSF participants explained that they did not have health care resources or medical services at the schools from which they come, and parents are not expecting the school to provide that kind of support. To address brokerage obstacles, school staff found they must balance friendliness that they try to achieve in their relationships with families and keeping professional boundaries, in order to not burn out.

Further, although our research highlights that school employees provided extensive brokerage, parents and school personnel did not always find points of connection between family needs and school employee brokerage. Families and school staff reported putting forth good effort at communication and meeting MSF children’s needs, yet a lack of coordination and communication due to language barriers, the impact of the domestic violence having differing backgrounds, lacking knowledge about healthcare, and encountering stress from being a migrant continue to threaten MSF families’ healthcare access. Other limitations to help-seeking and service provision for undocumented immigrants include not knowing the rights that individuals have when accessing care, privacy concerns, and not trusting systems will be responsive to their needs. Ultimately, a more coordinated way of communication and sharing ideas both between school staff and between staff and parents should be developed, especially one that meets the language needs of groups such as K’iche’-speakers.

Overall, MSF families experience structural vulnerability which puts them at increased health risk and impacts their access to health care. Currently, MSF families access Husky Health/Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program services at a lower rate than their non-MSF counterparts do. Likewise, MSFs are difficult to reach due to their migratory patterns and possible unauthorized residence in this country. As this pilot, exploratory research suggests and as supported by the Centers for Disease Control Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model, schools are an ideal setting to address healthcare access gaps for children with MSF status. Thus, the need for an intervention to address MSF children’s health needs and potential of the schools to fill this need, coupled with the fact that schools are compulsory, suggests a school-based program could be ideal. Deployed systematically across the U.S., a school health broker program in areas with migrants and others facing structural vulnerability could offer vast improvement in health and healthcare access. Finally, future research should consider how generalizable the brokerage of a vast array of employees who establishes deep relationships with the community and medical professionals found here is in other settings, as well as study the effects of an implemented broker model in schools.

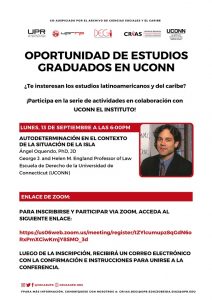

The first talk in the series, titled “Autodeterminación el el contexto de la situación de la isla,” was presented on 13 September 2021, by Angel Oquendo, George J. and Helen M. England Professor at the UConn School of Law. Oquendo gave emphasis to the need for new narratives to emerge about Puerto Rico’s political status if needed creative thinking is to occur about the present situation of crisis and how the island can replace the outmoded Estado Libre Asociado with a new model for its relationship with the United States and the world.

The first talk in the series, titled “Autodeterminación el el contexto de la situación de la isla,” was presented on 13 September 2021, by Angel Oquendo, George J. and Helen M. England Professor at the UConn School of Law. Oquendo gave emphasis to the need for new narratives to emerge about Puerto Rico’s political status if needed creative thinking is to occur about the present situation of crisis and how the island can replace the outmoded Estado Libre Asociado with a new model for its relationship with the United States and the world. Empire: Puerto Rican Workers on US Farms, by UConn Anthropology PhD and Professor of Anthropology at CUNY Staten Island, Ismael García-Colón. García-Colón’s talk on the challenges involved in researching and theorizing this topic was preceded by a brilliant appreciation of the book by UPR Professor Emeritus Silvia Alvarez-Curbelo.

Empire: Puerto Rican Workers on US Farms, by UConn Anthropology PhD and Professor of Anthropology at CUNY Staten Island, Ismael García-Colón. García-Colón’s talk on the challenges involved in researching and theorizing this topic was preceded by a brilliant appreciation of the book by UPR Professor Emeritus Silvia Alvarez-Curbelo. The Summer 2021 edition of

The Summer 2021 edition of