Contributed by Damián Deamici

After a hiatus due the COVID-19 pandemic, the Eyzaguirre Lecture returned to the University of Connecticut this fall. The lecture honors the memory of Professor Luis Eyzaguirre, who taught Spanish and Latin American literature at the institution for over 30 years. This was the first time that the lecture was held entirely online, which allowed for attendance across three continents and numerous different geographies. The virtual event was co-sponsored by the Department of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages, El Instituto, and the Center for Judaic Studies and Contemporary Jewish Life.

This year’s lecturer, Dr. Marilyn Miller, is Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Studies and Sizeler Family Professor of Judaic Studies at Tulane University. Her work on the discourses of slavery and race, the thorny notion of mestizaje, and her study of Jewish immigration to and between the Americas has had a defining influence on the fields of postcolonial, Latin American and Jewish studies. She is the author of Rise and Fall of the Cosmic Race: The Cult of Mestizaje in Latin America (University of Texas Press, 2004) and Port of no Return: Enemy Alien Internment in World War II New Orleans (LSU Press, 2021), as well as the editor of Tango Lessons: Movement, Sound, Image, and Text in Contemporary Practice (Duke University Press, 2014).

This year’s lecturer, Dr. Marilyn Miller, is Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Studies and Sizeler Family Professor of Judaic Studies at Tulane University. Her work on the discourses of slavery and race, the thorny notion of mestizaje, and her study of Jewish immigration to and between the Americas has had a defining influence on the fields of postcolonial, Latin American and Jewish studies. She is the author of Rise and Fall of the Cosmic Race: The Cult of Mestizaje in Latin America (University of Texas Press, 2004) and Port of no Return: Enemy Alien Internment in World War II New Orleans (LSU Press, 2021), as well as the editor of Tango Lessons: Movement, Sound, Image, and Text in Contemporary Practice (Duke University Press, 2014).

Dr. Miller’s lecture, titled “Eduardo Halfon and the Itinerary of Memory,” explored the work of author Eduardo Halfon, who was present in the audience and held a roundtable discussion with Professor Miller the following day. Halfon’s work eludes classification. He was born in Guatemala, to which his Polish grandfather migrated after surviving Auschwitz, an event fictionalized by Halfon in The Polish Boxer. His family relocated to the United States when Halfon was 10 years old to escape the Guatemalan civil war. Another ten years later he returned to Guatemala, where he began writing fiction in Spanish, the language of his childhood that was now almost foreign to him. Since then, his creative writing, which eludes generic classification, has received numerous awards, including the Premio Nacional de Literatura de Guatemala in 2018, and the Edward Lewis Wallant Award for his novel Mourning.

Dr. Miller’s lecture focused on aspects of Halfon’s work that make the construction of identity irreducible to stable categories, such as Guatemalan, Latino or Jewish. As such, her analysis focused on three elements of his narrative that challenge the stability of these classifications: masks, thresholds and itineraries. Her analysis presented the metaphor of masks as a search for belonging, of trying on different camouflages. The narrator of most of Halfon’s stories is a character bearing his own name, and whom Dr. Miller resourced to call Eduardo to differentiate him from the author. Eduardo’s own selfhood is presented as a mask or disguise, he assumes his identity depending on external circumstances, which allows him to inhabit many selves. This slipping back and forth among Jewish, Latino and Guatemalan identities allows Halfon’s work to avoid the single narrative that attempts to straightjacket Latin American literature within tropes of drug and border violence, magical realism, folklore and indigenous oppression. In its place, his identity is presented at a series of thresholds that the narrator navigates through the adaptation of several masks, including language. These negotiations of identity can be seen through the itineraries that force the characters to “pass as the other” in their geographical shifts. Dr. Miller’s ideas, much more expansive than what can be summarized here, challenge the constriction of selfhood to fixed identities. Through the analysis of Halfon’s work, she puts to rest the single-story narrative that attempts to encapsulate the diversity of a people into a single type. She presents another avenue for the construction of memory; multiple, elusive and free.

A roundtable discussion with Dr. Miller and Eduardo Halfon the next day, was moderated by Dr. Avinoam Patt, Chair of Judaic Studies and Director of the Center for Judaic Studies and Contemporary Jewish Life at the University of Connecticut, and expanded on the themes presented in the lecture. Halfon discussed the topics of language, belonging, memory, translation and the generic categorization of his work. He reinforced Dr. Miller’s conclusions of the elusive construction of identity and the apt metaphor of masks to describe it. The event was attended by dozens of students and faculty from UCONN and other institutions from around the globe.

On the whole, the lecture and the subsequent roundtable was a prodigious homage to the memory of Professor Eyzaguirre. Dr. Marilyn Miller’s extraordinary lecture, along with Eduardo Halfon’s willingness and candor answering questions of an eager and grateful audience, paid a memorable tribute to Professor Eyzaguirre’s legacy.

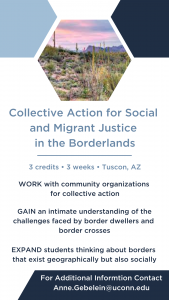

history of the sanctuary movement, and the unique needs of asylum seekers and child migrants.

history of the sanctuary movement, and the unique needs of asylum seekers and child migrants.

when I learned that I was one among six youth chosen to fly to Luanda by presidential invitation of the Government of Angola to be in direct discussion with Heads of state from various countries, including Portugal (Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa/ present on remarks link) and Costa Rica (Epsy Campbell Barr/ photo attached). I was the only representative of the Diaspora. The joy of being the sole representative across so many stellar candidates truly humbled me. There were students from all over the world and selected participants from US ivy league universities. And most importantly, the research work that caught their attention was my work that is somewhat critical of UNESCO and how countries from the Global South engage with UNESCO conventions and its standards. You can check out my opening remarks at the Biennale of Luanda’s Intergenerational Dialogue session with Heads of state here:

when I learned that I was one among six youth chosen to fly to Luanda by presidential invitation of the Government of Angola to be in direct discussion with Heads of state from various countries, including Portugal (Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa/ present on remarks link) and Costa Rica (Epsy Campbell Barr/ photo attached). I was the only representative of the Diaspora. The joy of being the sole representative across so many stellar candidates truly humbled me. There were students from all over the world and selected participants from US ivy league universities. And most importantly, the research work that caught their attention was my work that is somewhat critical of UNESCO and how countries from the Global South engage with UNESCO conventions and its standards. You can check out my opening remarks at the Biennale of Luanda’s Intergenerational Dialogue session with Heads of state here:  collaboration with youth (and their new questions). The more I work with youth, the more I realize that academic work in its nature may feel isolating, but it is collective. I am content that I was in dialogue with presidents. Still, the most meaningful part of my journey was to work directly with Angolan youth who do work about heritage, education, and human rights through art. I saw myself a lot in working with them. More than ever, it is time we think of the academy as a place of collective knowledge creation and attribution because if research is not for the benefit of people, why bother? I learned during lessons during my short time in Angola; the first one is that there are many Africas even within Angola. But the biggest one was how we must be careful in the work we do because folks are listening, and most importantly, we owe youth better. To me, being a UNESCO Youth representative became the responsibility to listen to learn how to do better. I am happy to keep the conversation going. You can find me at

collaboration with youth (and their new questions). The more I work with youth, the more I realize that academic work in its nature may feel isolating, but it is collective. I am content that I was in dialogue with presidents. Still, the most meaningful part of my journey was to work directly with Angolan youth who do work about heritage, education, and human rights through art. I saw myself a lot in working with them. More than ever, it is time we think of the academy as a place of collective knowledge creation and attribution because if research is not for the benefit of people, why bother? I learned during lessons during my short time in Angola; the first one is that there are many Africas even within Angola. But the biggest one was how we must be careful in the work we do because folks are listening, and most importantly, we owe youth better. To me, being a UNESCO Youth representative became the responsibility to listen to learn how to do better. I am happy to keep the conversation going. You can find me at  -me as a Ph.D. student, Stephany was an EAGLES Fellow, an NSF GK-12 Fellow, an NSF ACADEME Fellow, a CU Boulder ACTIVE Faculty Development and Leadership Fellow, an Outstanding Multicultural Scholar/Crandall- Cordero Fellow, and won a prestigious Ford Foundation Fellowship from the National Academies. Additionally, she was the inaugural recipient of the Inspiring STEM Equitability Award and a Woman of Innovation by the Connecticut Technology Council. Stephany has presented on her work in diversity and outreach in numerous national forums and has contributed as a team member or collaborator on numerous NSF-funded research studies on diversity and outreach topics.

-me as a Ph.D. student, Stephany was an EAGLES Fellow, an NSF GK-12 Fellow, an NSF ACADEME Fellow, a CU Boulder ACTIVE Faculty Development and Leadership Fellow, an Outstanding Multicultural Scholar/Crandall- Cordero Fellow, and won a prestigious Ford Foundation Fellowship from the National Academies. Additionally, she was the inaugural recipient of the Inspiring STEM Equitability Award and a Woman of Innovation by the Connecticut Technology Council. Stephany has presented on her work in diversity and outreach in numerous national forums and has contributed as a team member or collaborator on numerous NSF-funded research studies on diversity and outreach topics. established with a major gift to UCONN by John and Donna Krenicki, with the aim of establishing an innovative interdisciplinary curriculum in areas like entertainment engineering and industrial design. Paricio received his bachelor’s degree from the Complutense University of Madrid, followed by a master’s in industrial design from the Pratt Institute and a PhD from the Complutense University, with a dissertation on Freehand Drawing in Industrial Design. He taught at the Rhode Island School of Design, Ohio University, The Art Institute of Pittsburgh, The Art Institute of Colorado, Pratt Institute and Parsons School of Design. He has practiced product design and exhibit design in New York City, Denver and Madrid, Spain, and has helped write patents and developed concepts for Colgate Palmolive among other companies. He has written two books, Perspective Sketching and Hybrid Drawing Techniques for Interior Design.

established with a major gift to UCONN by John and Donna Krenicki, with the aim of establishing an innovative interdisciplinary curriculum in areas like entertainment engineering and industrial design. Paricio received his bachelor’s degree from the Complutense University of Madrid, followed by a master’s in industrial design from the Pratt Institute and a PhD from the Complutense University, with a dissertation on Freehand Drawing in Industrial Design. He taught at the Rhode Island School of Design, Ohio University, The Art Institute of Pittsburgh, The Art Institute of Colorado, Pratt Institute and Parsons School of Design. He has practiced product design and exhibit design in New York City, Denver and Madrid, Spain, and has helped write patents and developed concepts for Colgate Palmolive among other companies. He has written two books, Perspective Sketching and Hybrid Drawing Techniques for Interior Design.

bbean or have an affinity to learn more about the Latino and/or Caribbean diasporas. LCI was born from the efforts of many current and former UConn staff and faculty, including Dr. Diana Rios, an associate professor in ELIN.

bbean or have an affinity to learn more about the Latino and/or Caribbean diasporas. LCI was born from the efforts of many current and former UConn staff and faculty, including Dr. Diana Rios, an associate professor in ELIN.