Contributed by Katerina Gonzalez Seligmann.

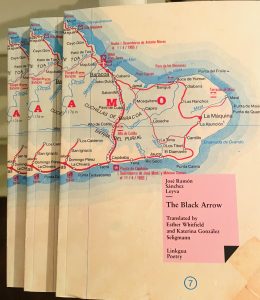

The Black Arrow, a book of poems reflecting on the U.S. naval based in Guantánamo by José Ramón Sánchez Leyva that I translated with Esther Whitfield was recently released by Linkgua Ediciones. José Ramón Sánchez ventures into territory that few Cuban writers have approached: the naval base at Guantánamo Bay, leased from Cuba by the United States since 1903, under the coercive terms of the Platt Amendment, and used since 2002 to hold detainees in the so-called “war on terror.” A long-time resident of the Cuban city of Guantánamo, less than twenty miles from the base, Sánchez reflects on the history and continued presence in his country of the U.S. military, the detention camps and the land-mined fence line that separates the base from Cuba.

To share the news with you about this book, I include here a selection from its translator’s note that Whitfield and I co-authored as we reflected on how we understand the book we collaborated to bring into being in English.

Isolated though it may be, the Guantánamo that the author inhabits in these poems is expansive in its history, geography, and imaginative connections. It is the Guantánamo of long-standing imperialist designs and resistance: of the Spanish-Cuban-American War that ended colonial rule in Cuba and established the continuing American presence at Guantánamo, through the lease in perpetuity that has been a vehement theme in the anti-imperialist rhetoric of the Cuban Revolution since Fidel Castro first seized power. It is the hostile space of the post-1959 years during which the base has been framed as a threat to Cuba, whose military forces surveil a borderland impassable to Cuban citizens other than the few elderly base workers permitted to continue crossing back and forth until the last of them retired in 2012— and the wild animals who, in several of the author’s poems, graze there freely. Also unhindered by the border, until systems were upgraded on the base, were radio and television channels that allowed residents of Cuban Guantánamo to listen into English-language broadcasts unavailable elsewhere in the country, allowing them what the author calls, in “The Channel from the Base,” “the exclusive luxury” of “an outside world/ beyond our socialist republic.” Post 9/ 11 Guantánamo, that has held over seven hundred detainees as “enemy combatants,” is well-known worldwide but has had a scant presence in the Cuban press. The experience of the detainees — as Muslims, as prisoners, and in many cases as poets—is, however, deeply compelling to the author. Sánchez Leyva pieces together what he can about this experience from a haphazard and multivocal archive: memories of a childhood in which light, sound, and broadcast signals from the base reached into the surrounding areas; printed histories and maps; official records pertaining to the base’s creation and development; oral reports from residents of Guantánamo province; leaked documents pertaining to detention operations; and detainees’ poetry.